Tag Archives for " ruby "

Mastering Ruby Regular Expressions

Ruby regular expressions (regex for short) let us find specific patterns inside strings, with the intent of extracting that data for further processing. Two common use cases for regular expressions are validation and parsing.

For example, think about an email address, with regular expressions we can define what a valid email address looks like. That will make our program able to differentiate a valid email address from an invalid one.

Regular expressions are defined between two forward slashes, to differentiate them from other language syntax. The most simple expressions just match a word or even a single letter, for example:

|

1 2 |

# Find the word 'like' "Do you like cats?" =~ /like/ |

This will return the index of the first occurrence of the word if it was found or nil otherwise. If we don’t care about the index we could just use the String#include? method.

Character Classes

A character class lets you define either a range or a list of characters to match. For example, [aeiou] matches any vowel.

Example: Does the string contain a vowel?

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

def contains_vowel(str) str =~ /[aeiou]/ end contains_vowel("test") # returns 1 contains_vowel("sky") # returns nil |

This will not take into account the amount of characters, we will see how to do that soon.

Ranges

We can use ranges to match multiple letters or numbers without having to type them all out. In other words, a range like [2-5] is the same as [2345].

Some useful ranges:

- [0-9] matches any number from 0 to 9

- [a-z] matches any letter from a to z (no caps)

- [^a-z] negated range

Example: Does this string contain any numbers?

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

def contains_number(str) str =~ /[0-9]/ end contains_number("The year is 2015") # returns 12 contains_number("The cat is black") # returns nil |

Remember: the return value when using =~ is either the string index or nil

There is a nice shorthand syntax for specifying character ranges:

- \w is equivalent to [0-9a-zA-Z_]

- \d is the same as [0-9]

- \s matches white space (tabs, regular space, newline)

There is also the negative form of these:

- \W anything that’s not in [0-9a-zA-Z_]

- \D anything that’s not a number

- \S anything that’s not a space

The dot character . matches everything but new lines. If you need to use a literal . then you will have to escape it.

Example: Escaping special characters

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

# If we don't escape, the letter will match "5a5".match(/\d.\d/) # In this case only the literal dot matches "5a5".match(/\d\.\d/) # nil "5.5".match(/\d\.\d/) # match |

Modifiers

Up until now we have only been able to match a single character at a time. To match multiple characters we can use pattern modifiers.

| Modifier | Description |

|---|---|

| + | 1 or more |

| * | 0 or more |

| ? | 0 or 1 |

| {3,5} | between 3 and 5 |

We can combine everything we learned so far to create more complex regular expressions.

Example: Does this look like an IP address?

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

# Note that this will also match some invalid IP address # like 999.999.999.999, but in this case we just care about the format. def ip_address?(str) # We use !! to convert the return value to a boolean !!(str =~ /^\d{1,3}\.\d{1,3}\.\d{1,3}\.\d{1,3}$/) end ip_address?("192.168.1.1") # returns true ip_address?("0000.0000") # returns false |

Exact Matching

If you need exact matches you will need another type of modifier. Let’s see an example so you can see what I’m talking about:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

# We want to find if this string is exactly four letters long, this will # still match because it has more than four, but it's not what we want. "Regex are cool".match /\w{4}/ # Instead we will use the 'beginning of line' and 'end of line' modifiers "Regex are cool".match /^\w{4}$/ # This time it won't match. This is a rather contrived example, since we could just # have used .size to find the length, but I think it gets the idea across. |

If you want to match strictly at the start of a string and not just on every line (after a \n) you need to use \A and \Z instead of ^ and $.

Capture Groups

With capture groups, we can capture part of a match and reuse it later. To capture a match we enclose the part we want to capture from the regular expression in parenthesis.

Example: Parsing a log file

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

Line = Struct.new(:time, :type, :msg) LOG_FORMAT = /(\d{2}:\d{2}) (\w+) (.*)/ def parse_line(line) line.match(LOG_FORMAT) { |m| Line.new(*m.captures) } end parse_line("12:41 INFO User has logged in.") # This produces objects like this: # <struct Line time="12:41", type="INFO", msg="User has logged in."> |

In this example, we are using .match instead of =~. This method returns a MatchData object if there is a match, nil otherwise. MatchData has many useful methods, check out the documentation!

You can access the captured data using the .captures method or treating the MatchData object like an array, the zero index will have the full match and consequent indexes will contain the matched groups.

We can also have non-capturing groups. They will let us group expressions together without a performance penalty. You may also find named groups useful for making complex expressions easier to read.

| Syntax | Description |

|---|---|

(?:...) |

Non-capturing group |

(?<foo>...) |

Named group |

Example: Named Groups

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

m = "David 30".match /(?<name>\w+) (?<age>\d+)/ m[:age] # => "30" m[:name] # => "David" |

Look ahead / Look behind

This is a more advanced technique that might not be available in all regex implementations. Ruby’s regular expression engine is able to do this, so let’s see how take advantage of that.

Look ahead lets us peek and see if there is a specific match before or after.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| (?=pat) | Positive lookahead |

| (?<=pat) | Positive lookbehind |

| (?!pat) | Negative lookahead |

| (?<!pat) | Negative lookbehind |

Example: is there a number preceded by at least one letter?

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

def number_after_word?(str) !!(str =~ /(?<=\w) (\d+)/) end number_after_word?("Grade 99") |

Ruby’s Regex Class

Ruby regular expressions are instances of the Regex class. Most of the time you won’t be using this class directly, but it is good to know

|

1 2 |

puts /a/.class p Regexp.new("a") |

Formatting long regular expressions

Complex regular expressions can get pretty hard to read, so it would be helpful if we broke them into multiple lines. We can accomplish this by using the ‘x’ modifier. This format also allows us to use comments.

Example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

LOG_FORMAT = %r{ (\d{2}:\d{2}) # Time \s(\w+) # Event type \s(.*) # Message }x |

Ruby regex: Putting It All Together

Regular expressions can be used with many Ruby methods.

- .split

- .scan

- .gsub

- and many more…

Example: Get all words from a string using .scan

|

1 2 |

"this is some string".scan(/\w+/) # => ["this", "is", "some", "string"] |

Example: Capitalize all words in a string

|

1 |

str.gsub(/\w+/) { |w| w.capitalize } |

Conclusion

Ruby regular expressions are amazing but sometimes they can be a bit tricky. Using a tool like rubular.com can help you build your ruby regex in a more interactive way, it also includes a ruby regular expression cheatsheet that you will find very useful. Now it’s your turn to crack open that editor and start coding.

Oh, and don’t forget to share this with your friends if you enjoyed it, so more people can learn 😉

Using Struct and OpenStruct

Sometimes you just want an object that can store some data for you, the struct class is very useful in that situation.

Getting Started

To create our Struct we pass in a series of symbols, which will become the instance variables of this class. They will have accessors defined by default (both for reading and writing).

|

1 |

person = Struct.new(:name, :age, :gender) |

Now you can create new objects of this class with new:

|

1 2 3 |

john = person.new "john", 30, "M" puts john.age puts john.class |

Structs can be tricky

There are some differences with a “normal” class that you need to be aware of. For example, you may have noticed that the class of our john object is just “Class”. To change this, we can do one of the following:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

# Option 1 - Assign to a constant Person = Struct.new(:name, :age, :gender) # Option 2 - Subclass class Person < Struct.new(:name, :age, :gender) end |

Both of these options will cause our new objects to have the class name we want. Another caveat with Struct-generated classes is that they won’t enforce the correct number of arguments for the constructor. For example, with a proper class you would see this error:

|

1 2 |

ArgumentError: wrong number of arguments (0 for 3) from (pry):214:in 'initialize' |

But if you are using Struct the missing arguments will be nil, so keep this in mind when working with Struct.

|

1 2 |

Person.new "peter" => #<struct Person name="peter", age=nil, gender=nil> |

Using OpenStruct

If you just need a one-off object, then you should consider using OpenStruct instead.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

require 'ostruct' cat = OpenStruct.new(color: 'black') puts cat.class puts cat.color |

Warning: OpenStruct is slow and you shouldn’t use it on production apps, according to schneems on this reddit comment. Also I found this blog post that has some benchmarks supporting this.

The main difference with Struct is that it just produces objects, in other words, you can’t call cat.new in the example above to get more objects like it.

Conclusion

As long as you are aware of the special characteristics of each of these clases you will be fine. Now go and start coding!

Working with files and folders

Data processing is a common task in programming. Data can come from many places: files, network, database, etc. In this post you will learn how to work with files and folders in Ruby.

Reading files

The file class allows you to open a file by simply passing in the file name to the open method:

|

1 |

file = File.open("users.txt") |

Since File is a sub-class of the IO class, you can work with file objects using IO methods. For example, using gets you can read one line at a time, and using read you can read the whole file or a specified number of bytes.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

# Read the first line file.gets # => "user1\n" # Go back to the start of the file file.rewind # Read the whole file file.read # => "user1\nuser2\nuser3\n" # We are done, close the file. file.close |

You will need to remember to call close on your file, so the contents are flushed to disk (if you wrote to it) and the file descriptor is made available.

If you want to read the whole file with just one line of code you can use File.read, in this case you don’t need to close the file. There is also a File.write counterpart to this method.

|

1 2 |

data = File.read("users.txt") # => "user1\nuser2\nuser3\n" |

If you want to process the file one line at a time, you can use the foreach method:

|

1 |

File.foreach("users.txt") { |line| puts line } |

Writing to files

File writing is pretty easy too. When opening a file for writing, we need to add the “w” flag as the second argument.

|

1 |

File.open("log.txt", "w") { |f| f.write "#{Time.now} - User logged in\n" } |

This will rewrite the previous file contents. If you want add to the file, use the “a” (append) flag.

Another way to write data into a file is to use File.write:

|

1 |

File.write("log.txt", "data...") |

File & directory operations

Other than reading and writing there are other operations you may want to do on files. For example, you may want to know if a file exist or get a list of files for the current directory. Let’s see a few examples:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 |

# Renaming a file File.rename("old-name.txt", "new-name.txt") # File size in bytes File.size("users.txt") # Does this file already exist? File.exists?("log.txt") # Get the file extension, this works even if the file doesn't exists File.extname("users.txt") # => ".txt" # Get the file name without the directory part File.basename("/tmp/ebook.pdf") # => "ebook.pdf" # Get the path for this file, without the file name File.dirname("/tmp/ebook.pdf") # => "/tmp" # Is this actually a file or a directory? File.directory?("cats") |

The last example makes more sense if we are looping through the contents of a directory listing.

|

1 2 3 4 |

def find_files_in_current_directory entries = Dir.entries(".") entries.reject { |entry| File.directory?(entry) } end |

Using Dir.glob you can get a list of all the files that match a certain pattern, here are some examples:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

# All files in current directory Dir.glob("*") # All files containing "spec" in the name Dir.glob("*spec*") # All ruby files Dir.glob("*.rb") |

Documentation links

Mastering Ruby Arrays

Arrays are a fundamental data structure that stores data in memory. In Ruby you can store anything in an array, from strings to integers and even other arrays. The elements in an array are accessed using their index, which starts at 0.

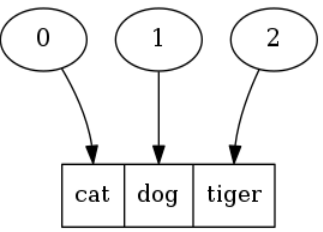

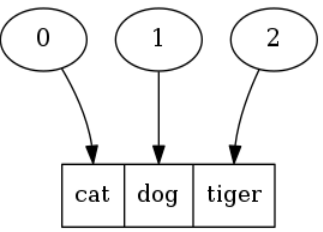

This is what an array containing the words “cat”, “dog” and “tiger” would look like:

Ruby Arrays – Basic Operations

To work with an array you will have to create one first, there are multiple ways to do it.

Initialize an empty array:

|

1 2 3 |

# Both of these do the same thing, but the second form is prefered users = Array.new users = [] |

Initialize an array with data:

|

1 |

users = ["john", "david", "peter"] |

Alternatively, you can avoid having to type the quotes for every string by doing this:

|

1 2 |

# Same effect as last time, but much faster to type users = %w(john david peter) |

Now that we have an array the next step would be accessing the elements that it contains.

Access array element by index:

|

1 2 3 |

users[0] # First element of the array users[1] # Second element of the array users[2] # Third element of the array |

You can also use the first and last methods:

|

1 2 |

users.first # First element of the array users.last # Last element of the array |

At this point you may want to add items to your array:

|

1 2 3 |

# Both of these have the same effect, << is preferred. users.push "andrew" users << "andrew" |

And finally, here is how you delete elements from your array:

|

1 2 |

last_user = users.pop # Removes the last element from the array and returns it user.delete_at(0) # Removes the first element of the array |

There is also the shift / unshift methods, which are similar to pop/push but take or add elements in front of the array.

|

1 2 |

users.unshift "robert" # Adds an element in front of the array users.shift # Removes the first element of the array and returns it |

Here is a small cheatsheet for you:

|

1 2 3 4 |

init -> Array.new, [], %w read -> [0], first, last add -> push, <<, unshift remove -> pop, delete_at, shift |

Iterating Over Ruby Arrays

Now that you have got an array wouldn’t it be nice if you could enumerate its contents and print them? Well the good news is that you can!

Example: Print your array using each

|

1 |

users.each { |item| puts item } |

Most of these looping operations are available thanks to the Enumerable module, which is mixed into the Array class by default.

Example: Capitalize every word in our Array using map.

|

1 2 |

users = users.map { |user| user.capitalize } user = users.map(&:capitalize) # This syntax is available since Ruby 1.9 |

The map method doesn’t modify the array in-place, it just returns a new array with the modified elements, so we neeed to assign the results back to a variable. There is also a map! (notice the exclamation point) method which will modify the array directly, but in general the simpler version is preferred.

Another thing you may want to do is find all the items in your array that fit certain criteria.

Example: Find all the numbers greater than 10:

|

1 2 3 |

numbers = [3, 7, 12, 2, 49] numbers.select { |n| n > 10 } # => 12, 49 |

More Array Operations

There are a lot of things you can do using arrays, like sorting them or picking random elements.

You can use the sort method to sort an array, this will work fine if all you have is strings or numbers in your array. For more advanced sorting check out sort_by.

|

1 |

numbers = numbers.sort |

You can also remove the duplicate elements from an array, if you find yourself doing this often you may want to consider using a Set instead.

|

1 2 3 |

numbers = [1, 3, 3, 5, 5] numbers = numbers.uniq # => [1, 3, 5] |

If you want to pick one random element from your array you can use the sample method:

|

1 |

numbers.sample |

You may also want to “slice” your array, taking a portion of it instead of the whole thing.

Example: Take the first 3 elements from the array, without changing it:

|

1 2 |

numbers.take 3 numbers[0,3] |

Operations involving multiple arrays

If you have two arrays and want to join them you can do it like this.

|

1 2 3 |

# These do the same thing users.concat(new_users) # Faster since it works in-place users += new_users |

You can also remove elements from one array like this, where users_to_delete is also an array:

|

1 |

users = users - users_to_delete |

Finally, you can get the elements that appear in two arrays at the same time:

|

1 |

users & new_users |

Conclusion

Arrays are very useful and they will be a powerful ally by your side. Don’t forget to check out the documentation if you are unsure of what a method does.

Ruby Network Programming

Do you want to create custom network clients and servers? Or just understand how it works? Then you will have to deal with sockets. Join me on this tour of ruby network programming to learn the basics, and start talking to other servers and clients using Ruby!

So what are sockets? Sockets are the end points of the communication channel, both clients and servers have to use sockets to communicate.

The way they work is very simple:

Once a connection is established you can put data into your socket and it will make its way to the other end, where the receiver will read from the socket to process incoming data.

Socket Types

There are a few types of sockets available to you, the most common — the TCP Socket — will allow you to make connections to TCP-based services like HTTP or FTP. IF you have to use an UDP based protocol then you can use the UDP Socket.

The other types of sockets are a bit more esoterical, Unix sockets allow IPC (Inter-process communication) in Unix systems without the overhead of a full TCP connection.

Using Sockets in Ruby

Now that we know what sockets can do for us it is time to start using them. First, require the sockets library into your program:

|

1 |

require 'socket' |

To create a TCP socket you can use the TCPSocket class, as parameters you will need the destination IP address and port. This will attempt to establish a connection, if it can’t be established then you will get a Errno::ECONNREFUSED error.

|

1 |

socket = TCPSocket.new('google.com', 80) |

You should now be able to send messages through your socket, you will have to follow the protocol you are communicating with for the other end to be able to understand you.

|

1 2 |

socket.write "GET / HTTP/1.1" socket.write "\r\n\r\n" |

Many of the methods you will be using come from the parent classes of TCPSocket.

To read the response from the server you can use the recv method. You need to pass the amount of bytes that you want to read from the socket as a parameter.

|

1 |

puts socket.recv(100) |

There is a small problem, you might not get any data back and you app will appear to be doing nothing. The reason is that if there isn’t enough data to read, your program will ‘block’. This means it will wait until there is some data available or the server closes the connection. You may want to increase or decrease the amount of data you are reading depending on what protocol are you working with.

If blocking is an issue for you, check out the readpartial and read_nonblock methods from the IO class.

TCP Server

Let’s build a server! The process is similar to writing the client, but we will need to tell the socket to bind to an interface, then listen on it, and finally to accept incoming connections. The TCPServer class already does the first two for us.

Here is an example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

require 'socket' socket = TCPServer.new('0.0.0.0', 8080) client = socket.accept puts "New client! #{client}" client.write("Hello from server") client.close |

Our example server will be listening on port 8080 and greet a connecting client with a message. Notice how we can only accept one client and the program will end.

Accepting Multiple Clients

To be able to accept and respond to multiple clients, we will need a loop and some threads.

Example:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

require 'socket' PORT = 8081 socket = TCPServer.new('0.0.0.0', PORT) def handle_connection(client) puts "New client! #{client}" client.write("Hello from server") client.close end puts "Listening on #{PORT}. Press CTRL+C to cancel." while client = socket.accept Thread.new { handle_connection(client) } end |

That should start a new server that keeps listening until you stop it.

Conclusion

Playing with socket programming is fun! Now go create something cool and share it with everyone